Movie Info

Movie Notes

4-part Miniseries

Movie Info

- Director

- Ava DuVernay

- Run Time

- 4 hours and 56 minutes

- Rating

- R

VP Content Ratings

- Violence

- 7/10

- Language

- 8/10

- Sex & Nudity

- 5/10

- Star Rating

Relevant Quotes

Why, Lord, do you stand far off? Why do you hide yourself in times of trouble?In his arrogance the wicked man hunts down the weak, who are caught in the schemes he devises.

Is there no balm in Gilead? Is there no physician there? Why then is there no healing for the wound of my people?

Fifty-five years ago on a hot summer night in a Mississippi church Civil Rights activist Fanny Lou Hamer described her arrest and brutal beating by a state trooper. I still recall vividly her face and voice as she went on to describe her trial because she had trespassed in using a whites-only bathroom at a bus station. There in the jury box sat the cop who had permanently injured her with his rubber club. “White man’s justice,” she spewed out, as if she were expelling a piece of rotten fruit. There was a mixture of anger, scorn, and resentment in her voice.

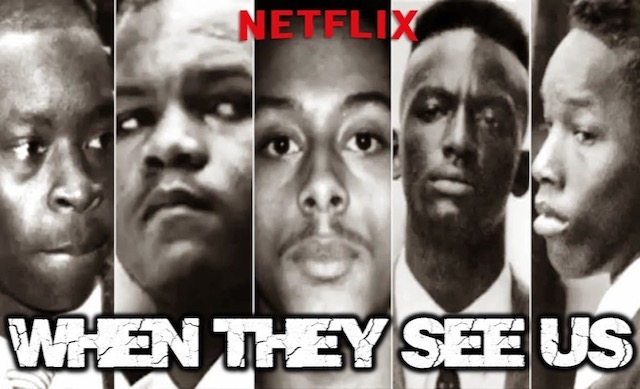

All of the above came flooding back to me as I watched the first episode of Ava DuVernay’s dramatic 4-part series. I could still hear Ms. Hamer’s powerful contralto voice, its volume and scornful tone increasing as each of the remaining episodes unfolded in vivid detail. Mississippi justice was notorious for its injustice in the 1960s, but the 5 African American young men standing trial for the rape and brutal assault on a white female jogger took place 25 years later in a city from which some of the white CR volunteers for the Mississippi Summer Project had come! New York City, a part of the American myth of “the Melting Pot,” the place where people from all nations and stations in life came for a life of freedom and equality! Apparently, many in the New York Police Department did not buy into the myth, their hearts as twisted by racism as those of the Mississippi cops of the 60s. Clearly racism is not a matter of geography!

Ava DuVernay is both director and co-author of the mini-series. Her well-received Selma dealt with the Dream Speech maker and his associates who fought against Alabama racism, and her new Netflix series demonstrates that 25 years later blacks still lived in a racist nightmare rather than the dream envisioned by Dr. King. The films chronicle the events of April 19, 1989 when Trisha Melli, a 28-year-old investment banker, was brutally raped and left for dead in the North Woods of Central Park and then the vicious interrogation of the boys, their trials and media storm surrounding it, and numerous events when they were incarcerated, paroled, and finally exonerated after the real rapist confessed to the crime.

One of the characters is very much aware of the irony that the very night of the round-up of the boys the police had in custody the rapist charged with at least two other assaults but, blinded by the way they looked at the five boys (note the film’s title), did not bother to ask him if he had raped Ms. Melli or even think of linking him to her, even though the way that he beat and raped the others was identical to Ms. Melli’s attack.

Known in the media as “The Central Park 5,” the film makers do their best to make us see them not as anonymous numbers, but as the young individuals that they were, full of energy and hopes, their lack of experience as to how society works leaving them vulnerable to the tactics about to be employed by the cops against them– Antron McCray (Caleel Harris, young Antron; Jovan Adepo, adult); Yusef Salaam (Ethan Herisse, young Yusef; Chris Chalk, adult); Raymond Santana (Marquis Rodriguez; Freddy Miyares); Kevin Richardson (Asante Blackk, young Kevin; Justin Cunningham); and Korey Wise (Jharrel Jerome, both young & adult Wise). These actors and the many others who round out the large cast are totally convincing in their creation of the horrific events that follow.

The adjective “harrowing,” used by more than one critic, best describes the effect of watching how the police use intimidation, threats, lies, and physical deprivation during the 24 hours before the boys are allowed a lawyer. Although some of the parents accompany their boys, they are at times tricked into leaving the room, something they will come to regret. All the suspects insist on their innocence, and none of their initial testimony reveals any knowledge of the details of the rape. One boy has scratches on his face, allegedly from his struggle with the victim, and though he explains that they came when a policeman tackled him and hit him with his helmet, the interrogator refuses to believe him. And apparently at the trial the lab report that there was no trace of the victim’s DNA on the boy was not revealed.

The film leaves no doubt that once in the park the exuberant boys did some harassing (or “wilding”) of cyclists, but not anything more serious. Linda Fairstein (Felicity Huffman), the head of the Manhattan District Attorney’s sex crimes unit, seeing the youth as black thugs, has no doubt that the underhanded tactics she and her squad of detectives use are appropriate. The cops are so aggressive, acting more like Gestapo agents than the police of a democracy, that one of the fathers, Bobby (Michael Kenneth Williams), convinced that the cops will kill his son if he continues to insist on his innocence, pleads with the terrified boy to sign the confession. The boy holds out for a while longer, but then gives in, signing the prepared confession while being videotaped. This will lead to later shame on the part of the father, a divorce, and the refusal of the paroled son to reconcile with him until just before the man dies of his debilitating illness.

Elizabeth Lederer (Vera Farmiga), the lead attorney for the prosecution, is disturbed by the lack of physical evidence that any of the boys are guilty of rape and the conflicting testimony in the boys’ so-called confessions. However, the cops and public pressure wear her down, and she goes along, applauded by the media and the public, eager to see the culprits punished. Knowing full well the weakness of her case, she sees the videotaped confessions as the ticket to victory. Her giving in when her instincts tell her otherwise, eventually in the courtroom referring to the boys as “animals,” will remind some of Pontius Pilate’s washing his hands and going along with the crucifixion of the Galilean whom he knew was innocent.

The first three episodes deal with the arrest and interrogation, trial, and parole of the four who were sent to a “juvie” detention center, and the last focuses mainly upon the ordeal of Korey Wise (Jharrel Jerome), who at 16 was old enough to be tried and sentenced as an adult. A marked man well before he is brought to the prison, he suffers horrible treatment by both guards and fellow prisoners. Because of the nature of his crime, everyone loathes him and wants to see him further punished. He has to enter solitary confinement to save his life. The only note of grace for him is the brief period at Attica where a white guard brings him some reading matter, a deck of cards and instructions for playing solitaire, and the promise of protection while out cleaning a recreation room. When Korey asks the man why he is so kind to him, the guard replies that he has a son about his age, and if he fell into such trouble, he hopes that someone would treat him as a human being. I was pleased that this was put into the script, lest some think the film makers were tarring all whites with the racist brush.

One of the saddest things about Korey’s plight is that he wasn’t even in the park during the rape. It was his friend, and when the police took that boy into custody, Korey volunteered to go along to provide support. At the station the cops assumed he was part of those picked up in the park and refused to listen to his explanation that he had come along with his friend. During his long imprisonment Korey maintains his integrity by refusing to accept his false confession. He appears twice before the state parole board, and when they make it clear that he must first agree to his guilt before they will grant a parole, he refuses. The third year he doesn’t even bother to go to a hearing. He longs to “go home” (we hear this plea many times from the boys), but not at the cost of selling out to the unjust system.

The seeming miracle that saves the situation for Korey and his four companions stems from a chance encounter with fellow prisoner Matias Reyes (Reece Noi) in the inmates’ TV room. The two get into a brawl over the volume level of the TV and are forcibly separated by the guards. Later, at a different prison Korey is in the prison yard when Reyes spots him and reminds Korey of their past encounter. The latter reflects, remembers that they had indeed met, and not on friendly terms, and says he does not hold it against him anymore. Their reconciliation apparently leads Reyes to think over the injustice of Korey’s imprisonment—my basis for thinking this is his question, “Are you religious?”, indicating that he now is. Already in prison for raping several other women, Reyes apparently wants to clear his conscience and make things right for the wrongfully accused prisoner.

We see the paroled four receiving the almost unbelievable good news of Reyes’ confession—though out of prison the young men are still being punished by an unforgiving society—the four emerging from a Good Friday-dominated life into an Easter joy. Well, not quite, yet, the cops and prosecutor maintaining that all Reyes proves is that there were six gang rapists. Even when DNA tests are run and only that of Reyes’ links him to the victim, the authorities refuse to back down at first. There are two scenes of this denial, one involving one of the detectives, who stubbornly maintains the guilt of the youth, and the other with Linda Fairstein confronted by Elizabeth Lederer, the latter now totally convinced of the youth’s innocence. Ms. Fairstein has profited from the fame she garnered from the boys’ plight by writing several crime novels. She refuses to admit any undue pressure had been applied to the boys or to accept the DNA report that only Reyes was guilty.

Fortunately, District Attorney Robert Morgenthau (Len Cariou), who was also in office when the boys were tried years earlier, does show regret. The courts exonerate the boys and remove them from the curse of the state’s registry of sex crime offenders. The police, however, refuse to offer an apology for the blighted years of the boys’ lives, and it will take 12 years of legal battling for the men to receive financial compensation for those wasted years. Even when they are granted by the court an award, it comes with the police admitting to no guilt nor offering an apology, thus proving again that institutional racism is alive and well.

Ava DuVernay’s film confirms what #Black Lives Matter has been contending concerning the nation-wide series of police shootings of black males with almost no punishment of the killer. We should regard it as a cautionary film, taking serious its title as a plea for all of us to see those different from us as humans, not black thugs or “animals.” Her indictment of our legal system, which includes police and courts—and by association a press looking for sensationalism—sounds a prophetic alarm that must be heeded if our society is ever to find the “balm in Gilead” sought by the ancient prophet for his sick society. She is also following in the prophetic footsteps of writer James Baldwin, who, in such works as The Fire Next Time, wrote that to be a black man in America was to be in a constant state of rage. (See the documentary based on his writings, I Am Not Your Negro for more of his challenging insights.) In a way this miniseries can be seen as a factual expansion of his novel about a young black man unjustly imprisoned, If Beale Street Could Talk.

Ms. DuVernay has also dealt with this issue in her documentary that every American should watch, 13th, which provides the historical context or perspective for seeing the systematic racism that permeates our legal system. The title refers to the 13th Constitutional amendment, and the film’s subtitle or tagline “From Slave to Criminal in One Amendment,” describes how with the 13th Amendment African Americans shed their chains for the invisible ones of Jim Crow, shedding the latter thanks to the Civil Rights Movement, only to be re-enslaved by the get tough on crime legislation of the 90s, which has led to the huge incarceration of blacks.

In addition to this miniseries and Ava DuVernay’s other film, I hope you will also watch the follow-up TV special Opra Winfrey Presents: When They See Us Now in which she interviews the major cast members and the five men themselves—see the brief review of it that follows.

This review will be in the July issue of VP along with a set of questions for reflection and/or discussion. If you have found reviews on this site helpful, please consider purchasing a subscription or individual issue in The Store.