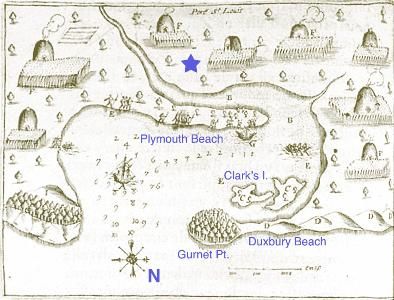

A HEARTBREAKING MAP: In 1605, explorer Samuel de Champlain had this detailed map drawn of the thriving Wampanoag village he visited along the shoreline where Pilgrims would land 15 years later. Between de Champlain’s visit and that historic 1620 landing by the Pilgrims, a virulent epidemic had raged through Wampanoag tribal lands that killed virtually all of the men, women and children in this particular village. The disease, an infection with symptoms similar to smallpox, was the result of early contacts with Europeans that spread the epidemic throughout the native communities. As the Pilgrims landed in 1620, they soon realized they were moving into what amounted to a ghost town. When Pilgrims explored the village’s ruins, they found ghastly evidence of the epidemic, including unburied skeletons of the last few native men and women to die.

.

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 26: Thanksgiving in 2020 will undoubtedly look different, but that doesn’t mean Americans won’t still be counting our blessings. After all, the tradition stretches back more than 400 years on this continent.

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 26: Thanksgiving in 2020 will undoubtedly look different, but that doesn’t mean Americans won’t still be counting our blessings. After all, the tradition stretches back more than 400 years on this continent.

Houses of worship across the country are encouraging Americans from their websites, offering a hopeful message in spite of the pandemic: “Give thanks anyway!”

In a Time of Pandemic, Recalling How Our Ancestors Coped

Most Thanksgiving holiday stories in schools, newspapers and magazines focus on the collision of cultures between natives and newcomers—and the exchanges of natural resources. The legacy of Columbus’s arrival in 1492 in the Caribbean ignited a series of “first encounters” that swept along the Atlantic shorelines of the American continents for more than a century.

The Smithsonian Institution’s educators summed up this revolutionary century under the theme Seeds of Change, which is the title of the Smithsonian’s superb book about this world-changing period. The discovery of new resources changed lives in both Old and New Worlds. Europeans had never seen a potato or tomato—which became defining staples of European cuisine—until after 1492. Natives of the Americas had never seen a horse until Europeans shipped them across the Atlantic from Europe—giving rise to the zenith of the Great Plains Indian nations. Without this collision of peoples, great advances in both continental cultures would not have been possible.

In its current Thanksgiving resource page for educators, the Smithsonian focuses on food and cultural traditions, describing the theme as: “From local harvest festival to national holiday, here are art and objects in the spirit of giving thanks.” (Note: If you’re looking for wonderful images to share on social media, check out that Smithsonian link! It’s a visual treasure trove.)

However, there’s much more to the Thanksgiving story in Plymouth, which is the focus of a worldwide 400th-anniversary celebration. (And, yes, there’s more on that 400th anniversary, below.)

A NEW VILLAGE ARISES IN A GHOST TOWN—For lessons about the Plymouth settlement, blue-colored notes have been added to de Champlain’s 1605 map showing locations relevant to the 1620 Pilgrim arrival. The blue star is the center of the subsequent Plymouth Colony.

So, what is the little-known story?

In 2020, the largely untold story of Thanksgiving is that the early banquet in Plymouth was held in the new town Pilgrims were building on—which was essentially a native burial ground.

Schoolchildren know about the historic meeting of Pilgrims and Wampanoags, often illustrated as healthy and co-existing in two thriving communities. However, such images do not capture the real setting of that first banquet.

When the Pilgrims finally decided to set up their new home near Plymouth Beach, the bustling Wampanoag village that explorer Samuel de Champlain had visited in 1605 was a ghost town. Fortunately, as the early Pilgrims cleared the ruins of the former native village, they were sensitive enough to halt their excavations in mounds where they found the natives’ human remains. In that earliest wave of settlement, their decision to halt such digging was respected by native people, even though the Pilgrims knew very little about these neighbors.

That’s not to diminish the fears and the dangerous violence that did break out between these newcomers and the people who had inhabited the lands for centuries. For example, one of the earliest encounters between the two peoples was a skirmish that included gunfire from the settlers.

The main reason greater violence was avoided is that most people were too sick to even think about fighting. Not only had the native people been suffering from lethal waves of contagion in the previous decade—decimating the Wampanoag and leaving their village at Plymouth abandoned—but the Pilgrims were similarly beset by devastating disease.

According to the surviving accounts, most of the Mayflower passengers and crew were seriously ill upon arrival. Many also were suffering from the effects of scurvy. Half of the new arrivals would die during the first winter. During the worst of the sickness, only a half dozen of the group were still healthy enough to feed and care for the rest. It was a desperate, life-and-death struggle. When the handful of physically able Pilgrims finished their community’s first house, it immediately became a hospital for ill Pilgrims. At the same time, the Pilgrims had to stake out and begin filling their own cemetery—on a grassy prominence above the beach.

The miracle is that there was any kind of “thanksgiving” meal at all in 1621! Historians say that, whatever the details of that first Plymouth observance, it was against long odds that anyone was still alive to celebrate.

That’s why, in 2020 and in the midst of a global pandemic, we can appreciate the larger miracle surrounding the Pilgrims’ first Thanksgiving: Every person in that region—native and newcomer alike—had been been living with the constant threat of lethal contagion. A mere 52 of the 102 Mayflower passengers survived the first year in Plymouth and were, therefore, able to celebrate the communal meal. The native people who participated were coming to a site filled with the ghosts of their own native families.

And still, as remarkable as it was—they managed to summon a spirit of gratitude and expressed thanksgiving together.

In 2020, the idea of gathering virtually with family and friends will be bittersweet. In addition to missing their in-person traditions, hundreds of thousands of families will remember loved ones who have perished from COVID since the 2019 year-end holidays.

Remembering those grieving and ailing natives and newcomers who gathered in Plymouth to give thanks four centuries ago may help to strengthen our own resolve.

Still—in the midst of our pandemic today—Americans will summon a spirit of gratitude and will give thanks.

400 YEARS IN THE MAKING: A THANKSGIVING HISTORY

Interested in learning more about the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower’s landing in Plymouth? The official website of the Plymouth 400 Commemoration offers educational resources and articles. From the UK, the Mayflower400 will offer, now through 2021, examinations of history from multiple angles, the experiences of those impacted by the Mayflower’s landing and more. From the Plimouth Plantation, an organization and museum in Plymouth, Massachusetts, commemorations will be held and new exhibits and resources offered.

That first Thanksgiving celebration melded two very different cultures. For the Wampanoag, giving thanks for the Creator’s gifts was an established custom. For European Pilgrims, English harvest festivals were about rejoicing, and after the bountiful harvest of 1621 and amicable relations between the Wampanoag and the Europeans, no one could deny the desire for a plentiful shared feast. The “first” Thanksgiving took place over three days, and was attended by approximately 50 Pilgrims and 90 Native Americans.

By the 1660s, an annual harvest festival was being held in New England. Often, church leaders proclaimed the Thanksgiving holiday. Later, public officials joined with religious leaders in declaring such holidays. The Continental Congress proclaimed the first national Thanksgiving in 1777, and just over one decade later, George Washington proclaimed the first nation-wide thanksgiving celebration, as “a day of public thanksgiving and prayer.” National Thanksgiving proclamations were made by various presidents through the decades, falling in and out of favor until Sarah Hale convinced President Abraham Lincoln to proclaim Thanksgiving as a federal holiday. Still, it wasn’t until 1941 that Thanksgiving was established permanently as the fourth Thursday of November.

Both the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade and America’s Thanksgiving Parade will be held this year, but spectators will be enjoying them virtually. Photo by Brecht Bug, courtesy of Flickr

FOOTBALL AND (VIRTUAL) PARADES & TURKEY TROTS

The National Football League has played games on Thanksgiving Day since its creation—and that tradition will continue in 2020. In 1924, Americans enjoyed the inauguration of both the “Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade,” held annually in New York City, and “America’s Thanksgiving Parade,” held in Detroit; this year, neither parade is cancelled, but both are discouraging or prohibiting spectators and offering, instead, virtual viewing options. In 2020, the theme for America’s Thanksgiving Parade will be “We Are One Together,” and will honor frontline workers and heroes of the COVID-19 crisis. Across the U.S., several cities host an annual Turkey Trot on Thanksgiving morning, welcoming runners of all ages to burn off some calories in anticipation of the day’s feast; this year, most of those events are being conducted virtually.

If you’re not up for making a time-intensive pie crust this year or have always secretly hated Aunt Betty’s yams, this is your opportunity to try something new! A Los Angeles Times article claims that pie can be outdone by something else this year—and offers three tempting alternatives—while another article’s headline proclaims that “It’s out with the old, in with the new for Thanksgiving 2020.” So go ahead—give yourself permission to try something new!

Recipes, décor and more: Find an assortment of recipes and menus (plus an at-home celebration guide) from Food Network, AllRecipes, Food & Wine and Epicurious.

Thanksgiving crafts: Adults can create DIY décor with help from HGTV, and kids can be entertained before the big dinner with craft suggestions from Parents, Parenting and Disney.