Photo by Melissa McMasters, used courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

By MARTIN DAVIS

Contributing Columnist

Along the swampy trails of the Congaree National Park, I first saw a bird with yellow feathers so bright that photographs fail to capture their true brilliance. That’s because the yellow reflects light, creating an aura that has thrilled birdwatchers for centuries.

This was my first encounter with a Prothonotary Warbler. It’s fair to say that that sighting was a near-religious experience, and it set me off on a life of watching birds.

Birdwatchers aren’t generally attuned to the mystical. They are intensely attentive to detail. Review the birdwatching guides produced by Audubon, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and Petersons—three of the more commonly used by amateurs and professionals alike—and you’ll see just how much detail. They describe intricacies of each bird’s song, their coloring, their flight patterns, where they tend to spend time. They provide detailed migration and breeding maps, so you know roughly when and where to find them. And you’ll find exquisitely detailed photographs and paintings of males, females, matures, and immatures.

The details, of course, matter. Ignore them, and you’re likely to overlook a spectacular bird like the Prothonotary Warbler as just another warbler—if you see it at all. But categorization carries a tyranny of its own. An obsession with categorizing color, flight patterns, and song can blind you to obvious questions.

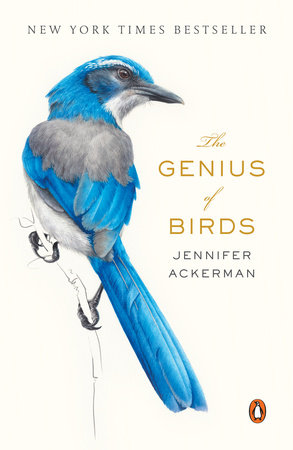

Enter Jennifer Ackerman, who in 2016 dropped a bombshell on the neatly classified world of birding. Her book The Genius of Birds describes the astonishing intellectual capacity of these feathered creatures. Discoveries brought about by people—often working on low budgets—who had the gumption to ask some different questions about the details they observed.

Referencing this research, Ackerman challenges us to see birds as our equals. “…in this book,” she writes, “the birds themselves are the heroes. … My hope is that by the time you finish these pages, the chickadee and the crow, the mockingbird and the sparrow, will look a little different to you. More like the bright fellow sojourners they are.”

In other words—no more watching birds simply to classify our beautiful friends on the wing. Rather, watching birds to try and understand, as well as learn from, our older evolutionary travelers. Doing so requires only that we pay more attention to the world around us.

How Do They Find My Feeder?

The feeders in our front yard are situated under a large Bradford Pear tree. We routinely see Cardinals, a wide range of finches, juncos, chickadees, downy woodpeckers, pileated woodpeckers, doves, titmice, crows, and blackbirds. Walk a couple hundred feet down the road, and on a good day you can spot a Coopers Hawk who enjoys keeping the neighborhood free of snakes and mice.

And on warm evenings, you can always hear, and occasionally see, the large barred owl who nests in our neighbor’s pine tree.

And yet, for all that diversity of life, Ackerman made me realize that I never asked the simplest of questions. How do these birds know to find this feeder?

The answer turns out to be far more complex than you probably knew.

The lowly chickadee—an attractive gray and white bird with a distinctive black cap—is so common that most of us walk by as many as a hundred a day and take no notice of them. I see them daily, and for too long just admired them for their attractive plumage. I’ve since learned that this diminutive bird has one of the most sophisticated calls known in the world of animals. The chickadee can alert other chickadees to predators, even letting them know their size and danger. They can call in reinforcements. And they can announce the discovery of a new food source.

And this is just the start.

They’re stunning acrobats. I’ve seen a chickadee literally run circles around a squirrel, causing him to fall off his limb, allowing the bird to recover the seed he sought.

As for storing seeds and finding them later, it seems the chickadee has no rival. They’ve been known to stash seeds across thousands of locations, and recall those locations up to six months later.

Is this intelligence? For years we felt it couldn’t be. Just look at the size of a bird’s brain. It’s simply too small. (And now you know the origin of the pejorative phrase, “bird brain.”) But there is no mistaking the innovations and complex language birds display. As it turns out, we were simply looking in the wrong place.

What we overlooked was brain activity at the level of the neuron. And by this measure, Ackerman says, birds “may be relatively small brained, but they are certainly not small minded.”

Seeing Anew

Birdwatching–and Ackerman’s book–remind us that seeing the remarkable doesn’t require pricey university degrees or trips to far-flung lands. And answers don’t require appeal to some undefinable force like “instinct,” which is often shorthand for: I just don’t have an answer.

You can attract more of life’s mysteries with a 10-dollar bird feeder from Home Depot and some sunflower seeds than you can possibly comprehend in your years here on earth.

The trick is learning to set your assumptions and received information aside, and dare yourself to ask the often obvious questions. For example: Why do Juncos—a diminutive bird seemingly easy prey for predators—spend so much time on the ground when feeding?

Why are owls so loud, but stay largely out of site?

How does a Cardinal survive, even thrive, when snow covers the ground and the temps drop well below freezing?

How can birds tell the difference between thistle seed and sunflower seed simply by flying past?

These are just some of the questions I find myself asking when watching the community of life that surrounds my feeders.

Try it yourself this spring. Just outside your window is a whole flock of fascinating questions about life. Consider the birds of the air—

Why are they here?

How do they live?

How do they survive the life-and-death challenges that come with the ever-changing seasons and looming predators?

What Jennifer Ackerman challenges all of us to do as we peer outside is to question our inherited conventions. There’s a deep and mysterious richness to life, she tells us—even among the birds in your own backyard.

We pulled down our feeders when we figured we were attracting red squirrels who found their way through our vents into the attic. But we’ve had some work done on the house that should have sealed up the vents and your column makes me think I should fill up those feeders again.