A table set for a Passover seder. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SUNSET MONDAY, APRIL 22: Tonight, Jews begin the joyous and deeply reflective festival of Passover—the most widely observed of all Jewish traditions.

Passover Basics

A few years ago, as Holidays & Festivals columnist for ReadTheSpirit magazine, I wrote an extensive Holidays section of the Michigan State University School of Journalism Bias Busters book called 100 Questions and Answers About American Jews with a Guide to Jewish Holidays.

Here is part of what I wrote in that book, which now is widely used by individuals and groups nationwide who want to know more about our neighbors’ faiths and cultures:

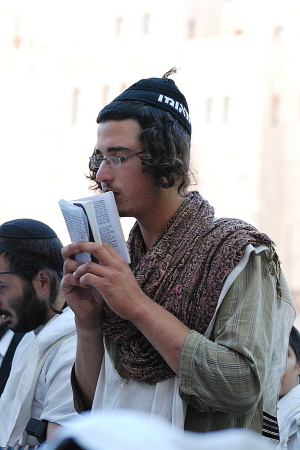

For eight days, starting with 15 Nissan, Passover recalls the ancient Israelites’ Exodus from slavery in Egypt. During Passover, Jewish families are reminded of when their ancestors were slaves in Egypt. Prior to the start of Passover, it is traditional for observant Jews to clean their homes so that not even a crumb of leavened food, or chametz, is present. While only one Seder is conducted in Israel, outside of Israel the first two nights of Passover have a Seder—a meal with symbolic foods, prayers, stories, songs and activities. In some homes, the Seder can last deep into the night. Most Jewish communities also offer “model Seders” for non-Jews who want to learn about this experience prior to Passover.

Many non-Jews are familiar from movies and TV shows with some of the Passover customs, such as the moment when the youngest in the household asks Four Questions, beginning with: “Why is this night different from all other nights?” Passover usually is experienced as a family reunion, a history lesson, an affirmation of survival and a time of reflecting on ways to help the vulnerable.

EGYPT, SLAVERY AND MATZAH

Matzah ball soup is traditional at Passover—and, this year, our magazine includes a personal story by author Rusty Rosman about making her traditional soup in a way that allows her transport it across country to family. gatherings.

Among the events in the biblical story recalled during the seder, Jews give thanks to G_d for “passing over” the homes of those whose doors were marked with lamb’s blood during the biblical Plague of the Firstborn, for helping them to escape safely from Egypt’s army and for eventually leading them to freedom.

Why is it so important to get rid of leavened products during this time?

According to Exodus, as the Israelites left Egypt they moved so quickly that their bread was not able to rise. To this day, unleavened matzah (spellings vary) is a staple element on seder tables and a symbol of this ancient festival.

Did you know? Matzo is made from flour and water that is mixed and baked in 18 minutes—to prevent the dough from rising. As matzo is such an important element of Passover, many Jews are trying to revive the art of homemade matzo. Baking matzo is a challenge; only 18 minutes are allowed between the mixing of flour and water to the finishing of baking. Elaborate measures are taken to ensure the mixture does not rise.

Throughout the holiday period, and in more traditionally observant households, the dishes and baking tools used for the Passover seder are reserved only for this time and have never come into contact with chametz. So, in many households—and in institutions that keep Kosher—there can be an enormous amount of preparation involved. In some cases, institutional ovens are “changed out” before the holiday period to ensure that cooks are using Kosher-for-Passover stoves. Most Kosher homes don’t have that luxury, so they go through an elaborate process of cleansing stoves before the holiday.

A lot of work goes into Passover!

During Passover, the Torah obligation of the Counting of the Omer begins. On the second day of Passover, keeping track of the omer—an ancient unit of measure—marks the days from Passover to Shavuot.